Today, what unseen movements and decisions are shaping what can and can’t be said, and what are the social and technological changes shaping these decisions? The work that can push the edges of tolerance or acceptance is both the most dangerous and the most necessary for delivering social change.

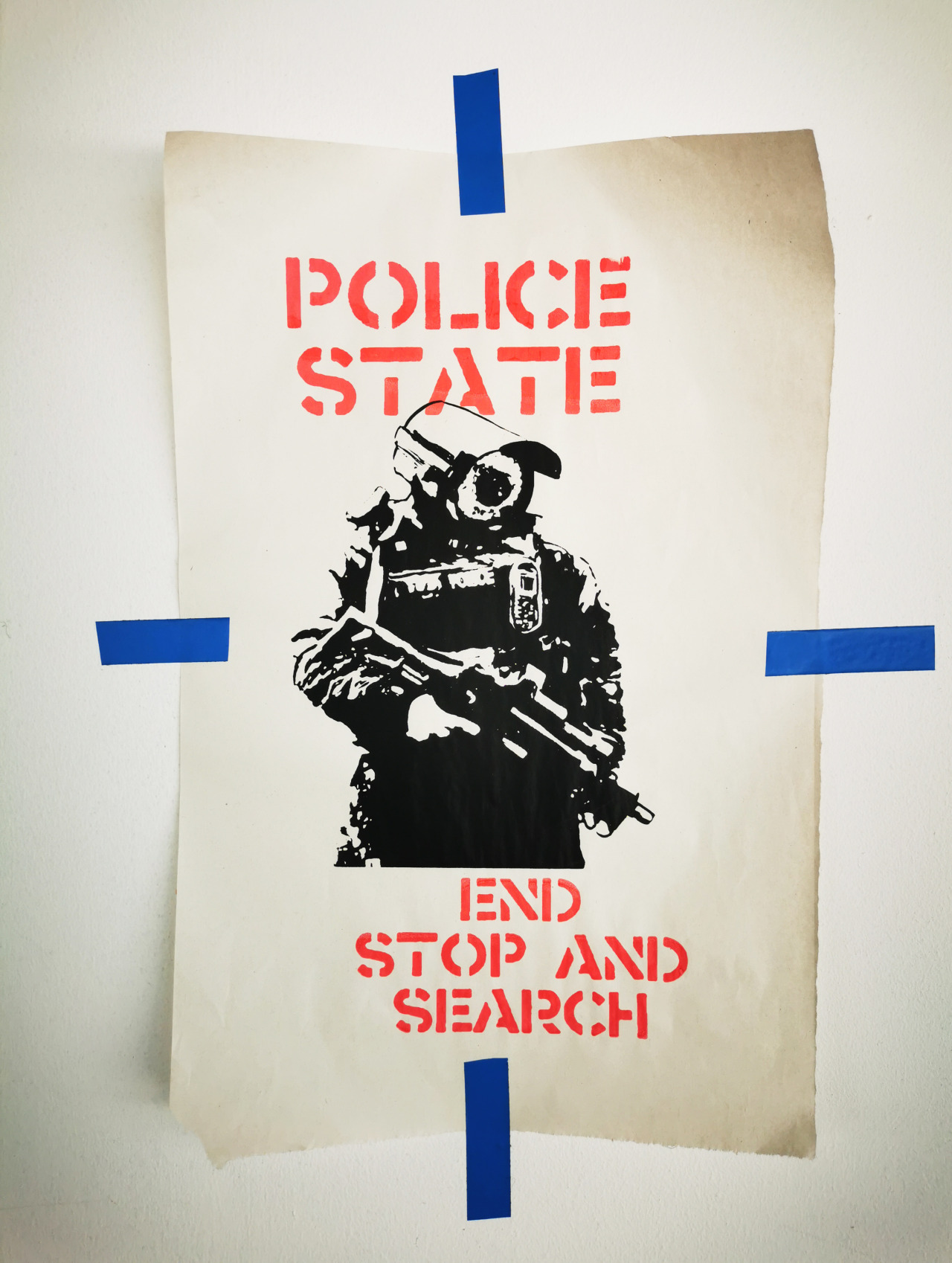

In Yorkshire, as in other regions, there are many artists producing progressive ideas and experimental work: speaking truths, challenging power and ruffling feathers. In Hull, artist Michael Barnes-Wynters and campaigning cartoonist and printmaker Sean Azzopardi were recently asked to remove a series of art installations from the windows of a shopping centre they’d taken over, part of a meanwhile spaces programme with East Street Arts. Following complaints from a nearby shopkeeper and members of the public about these works, which commented on a range of issues relating to Black Lives Matter, police violence and cronyism in the current Tory government, three consecutive installations have been taken down over a two-month period. In response to the incidents, Barnes-Wynters said attitudes to censorship and freedom of speech are fundamentally changing:

“We are in one of the most turbulent times in our human history, at that crucial tipping point where democracy becomes autocracy and so control is power – as censorship blatantly normalises hate speech and silences minorities. Both the public space and online spaces (especially the social media giants) censor artists’ works especially when we speak truth to power in the public realm.”

Barnes-Wynters feels that a desensitised public had become detached from making change happen, but that artistic forms of dissent can present a real threat to the ‘so-called’ status quo. As an instigator, broadcaster and early audio-visual artist, he has always occupied ‘a lane of crisis where there is that hint of danger’ and therefore recognises that artistic practice can be shaped in insidious ways. His previous work in the late 90s between Manchester, London and Tokyo was remarkably free from interference – creative work made in an atmosphere of outward-looking openness to new ideas.

By the time Hull 2017 had come around, the atmosphere had changed. Billboards made for the Capital of Culture year featured outward criticisms of Brexit (and even a nipple), that were censored by local traders and market organisers. After Barnes-Wynters and Azzopardi took on a space in the prominent Prospect Centre, operating as ‘RED contemporary arts: Nourishment Centre’, plans for the repurposed shopping centre space include showcasing community audio-visual work in the windows, a library of radical artworks, and a screen printing workshop for local people.

Following the complaints and subsequent de-installations, Barnes-Wynters and Azzopardi’s passion is undimmed; they continue to create in their space above the shop. Barnes-Wynters believes that artists must set their own boundaries and be their own censors, and ask ‘blunt, relevant and meaningful questions that tackle human suffrage, racism, gender exploitation, injustice, control and the hyper normalisation of humanity’. Being Black is a large factor, one that impacts upon his everyday experience as an artist:

“I am very aware of my physical Black body in the space which I know and see upsets some people (…) whenever a security guard comes in to speak to us, they always go straight to Sean, as (if) this Black body wouldn’t be responsible for the running of an art space!”

So, is there a difference between working in a designated art space or gallery, and a repurposed space in a shopping centre? Barnes-Wynters reflects, ‘For me it’s about having meaningful and transparent conversations with whomever has invited me, as said my boundaries and ingredients connect way beneath the skin… It’s important to remember I am not an island, and collaboration is queen’.

The enormous societal changes we’ve seen this year are magnifying existing trends in terms of how people occupy public spaces and spend their money (increasingly online). As town shopping centres decline, artists are brought in to fill the empty spaces. This idea isn’t new, but there’s a danger that if artists are encouraged to occupy commercial or otherwise publicly visible spaces, they might be encouraged to dial down their creative vision and political principles. In this increasingly online world of ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’, nurturing radical voices and ensuring freedom of expression is increasingly important. Barnes-Wynters stresses that we must continue to give platforms and mentoring support to marginalised voices through grassroots collaborative practices, especially in these divisive times.

In this increasingly online world of ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’, nurturing radical voices and ensuring freedom of expression is increasingly important.

Digital platforms and social media don’t provide a simple solution to these restrictions. In fact, many artists are experiencing more severe censorship online than ‘in real life’ public spaces. Aleksandra Karpowicz is a Polish-born artist and activist who has recently exhibited work in London, Vienna and on Venice’s Giudecca island. Her work addresses gender equality and she is currently campaigning against Poland’s new abortion laws. The artwork she uploads to Instagram is being censored on an almost weekly basis. She explains that while her work is about feminism and equal rights, the fact that she works with the human body and nudity means that she is regularly censored, even if she follows the rules.

Social media rules are designed partly to weed out false information and offensive content, but they can also discriminate and build a narrow world view, a way of seeing things that doesn’t represent everyone. Karpowicz explains how Instagram is discriminatory against women:

“As a simple example, you can show male nipples but you can’t show female nipples. If you dig deeper, it’s objectification and sexualisation of the female body. Images of naked flesh of beautiful models are allowed, but images of normal human bodies are flagged and censored. And now we’re living in a time of more fluid gender identities, the digital giants are just not keeping up. We’re seeing more and more censorship. And before non-binary or transgender people’s images are or are not censored, their gender is judged solely on the basis of prior prejudice. It is clear discrimination.”

Online censorship comes from human-made decisions and, increasingly, via algorithms. This means negotiation is not happening and artwork is simply being banned. Karpowicz feels there’s no accountability in big tech; that her voice is being silenced through algorithms and there is no one she can complain to. She claims that her followers don’t see her posts, her hashtags don’t work, and tagging is very difficult as her name doesn’t come up. From her perspective, ‘artists are being politically silenced in 2020’.

Tom Payne, artist, academic and co-director of live art company Doppelgangster, reflects on censorship since the 90s. He said the artist should be the one making the decisions on boundaries, not the funder or the owner of any digital or physical space:

“The role of the artist is to move towards the boundary and show us ways of crossing it. To provoke us to imagine ourselves on the threshold, and allow us, the viewer or spectator, to be uncertain from a position of relative safety while the artist teeters on the edge… I can choose to go to an exhibition or not. I can choose to close my eyes, turn my head, cover my ears, and head to the exit. So, I think the business of what should be permissible, especially in the relative safety of the spaces governed by the institutions of art, is less a question for the viewer, or the curator, and more a question for the artist.”

Payne adds that while the role of the artist is to break the mould, capitalism creates a framework in which breaking the mould can mean not getting paid. To address this, he feels we need to ‘flip the industry and rethink the hierarchies that govern creativity and drive ‘production’. But how does this artist-led approach to setting boundaries play out when exhibiting in public spaces?

Stephen Irving, co-director of Pineapple Black, based in a Middlesbrough shopping centre in Teesside, said curators often have difficult decisions to make. In 2019 he had to ‘censor’ an exhibition of work by Lidia Lidia, Girls World, that was attracting complaints. The work explored the realities faced by young girls using the scenes stages with Barbie dolls. Some of the imagery dealt with child prostitution and domestic abuse, which were intentionally provocative (e.g. Barbie being aggressively kicked by Ken), and exhibited within Pineapple Black’s window space 24/7. Irving explained that the complaints were nearly all ‘gut reactions’ – parents panicking that their children can see them – and that after the idea was explained to them (this info was available in the window beside the images – but not all read it), they saw the work for what it was and often praised it. Ultimately, Irving felt it was a bit too much for members of the general public, so they moved it out of the window and into the gallery space.

Irving reflects that in some ways, this was actually the best thing that could have happened. As the story about this made local, national and international news, it helped to get Pineapple Black and Lidia Lidia’s name out there (the artist was offered subsequent opportunities), and the questions raised in the exhibition were discussed ‘by more people across more platforms than they ever would have been by just being in our window’.

So, is encouraging public engagement and dialogue the answer? Irving said it is an ongoing curatorial debate. Curating at Pineapple Black has helped him identify unique challenges for showing art in non-art spaces like shopping centres:

“A permanent gallery has to think more long term, whereas a pop up can do what they want and then be gone. I think as an art gallery you need to draw a line between freedom of speech and your own moralities. But there is also the context to be considered – for example, I wouldn’t show a painting by a Nazi showing a Black person being oppressed – but I would show the same image if it was painted by a Black man to highlight oppression. I don’t think freedom of speech is as important as the context of speech.”

Back in Hull’s Prospect Centre, Azzopardi said the fight for freedom of speech would continue. He argues that any censorship of artistic expression should instil only resilience in artists: ‘When I’ve been censored before, it’s just made me want to make more and carry on’. He feels it’s important to keep offering people spaces to create and perform and ‘meet and cause trouble’, but sadly fears that the more local authorities are forced to sell buildings to balance government cuts, the spaces for collaboration and developing work will ‘diminish to non-existence’.

The lines in the battleground between artistic freedom of expression and populist worldviews are being redrawn. This rapidly shifting landscape is not easy to navigate, but paths are being found. Art, culture and creativity takes diverse forms across places and spaces, provoking new ideas in shopping centres, high streets and other public spaces. Working sensitively and creatively with commercial and corporate partners, curators and artists can leverage a diversity of expression and freedom of creativity that these public spaces have simply never had. This can generate not just new ideas, but new ways of seeing the world and create meaningful connections between communities.

Paul Drury-Bradey is a culture professional and writer based in Yorkshire.

This article has been co-published with Corridor8.

Other things!

-

News

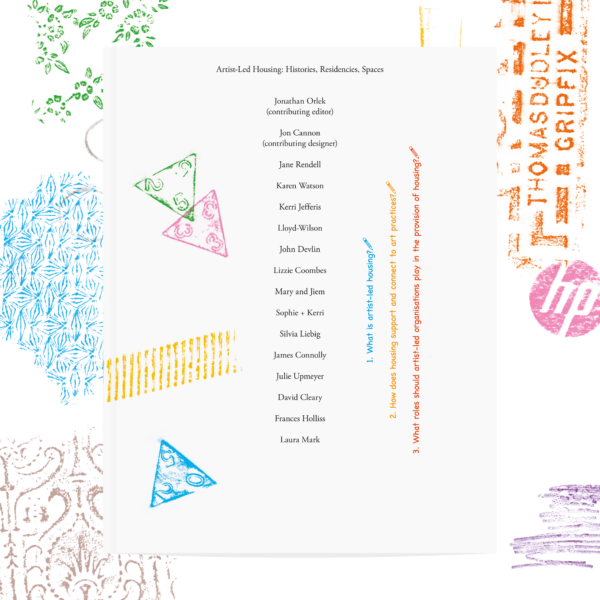

Artist-Led Housing: Histories, Residencies, Spaces - available to buy!

Architectural researcher Dr Jonathan Orlek's brand-new publication, Artist-Led Housing: Histories, Residencies, Spaces is now available to buy.

-

News

Taipei Residency: Artist Call Out

Are you an artist using sound and audio-visual media at the core of your practice? Do you want to collaborate with communities and other artists to develop new artworks? Apply now! Deadline 12pm, Sunday 5 May 2024.

-

News

Leeds Creative Labs Follow on Fund: Herfa Martina Thompson Dr Zoe Tongue

Visual artist Herfa Martina Thompson and Law lecturer Dr Zoe Tongue first collaborated as part of Leeds Creative Labs, a programme that partners artists and academics, initiated by the University of Leeds’ Cultural Institute and facilitated in partnership with East Street Arts.

-

History

Listen to the Sounds of New Briggate

Sounds of New Briggate is our podcast series - hosted by local people, telling local stories - which celebrates New Briggate, a unique and vibrant high street in the heart of Leeds.

-

News

Artist Mohammad Barrangi’s large-scale murals come to the streets of Leeds

We're working with Leeds-based, Iranian-born illustrator and printmaker Mohammad Barrangi to bring three large-scale paper murals to the streets of Leeds.

-

Artist support

Submit your publications to our exhibition and learning library

Do you make books or printed materials on artist-led housing, live/work spaces, civic practice or living archives? Contribute now! Together we can learn.